If you have read through articles online how to learn Chinese, you've have probably figured out by now full immersion is very good for language acquisitions, and learning any language can be difficult or easy depending on your approach. For this post we want to go over some common Mandarin mistakes language learners seem to struggle with or have some embarrassing and funny moments while using Mandarin to communicate.

For new and current Mandarin Students here is a list of common mistakes to remain mindful of.

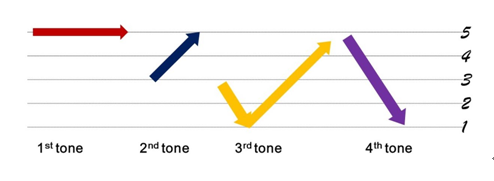

Misusing the 4 tones

The bane of your existence could be not mastering tones, which is a critical step at speaking good Mandarin. Tones are important because each word has at least 4 different meanings, so while you're speaking, one misuse of a tone can change your entire meaning which can lead to some rather funny language mishaps.

Examples:

Confusing 请问Qǐng wèn and 亲吻Qīn wěn

请问Qǐngwèn: means to ask. – 亲吻Qīn wěn: means to kiss

Confusing these two closely sounding two word combos could lead to obvious problems.

- 我可以问你吗?

Wǒ kěyǐ wèn nǐ ma?

- 我可以吻你吗?

Wǒ kěyǐ wěn nǐ ma?

Confusing: 老板Lǎobǎn and 老伴Lǎobàn

老板Lǎobǎn: boss – 老伴Lǎobàn: wife

You can imagine how this could become a funny face palm moment. Let's imagine you are at a dinner party with friends and colleagues, and in excitement you want to introduce your boss, but one slip of the tone, you utter that this is your spouse.

Word order

One common road to error that some Mandarin learners stumble down is not getting a hold of correct word order. Failing to put together proper word order only leave you with the fact that you are probably speaking broken Chinese. How to overcome this? You can try unscramble language exercises that prompts you to put words in sentences by correct order. These exercises are quite common in formal language textbooks and featured in some Chinese learning apps.

The typical word order for Mandarin is in the following structure: subject + verb + object.

Word order

我会去你家明天上午。

Wǒ huì qù nǐ jiā míngtiān shàngwǔ.

我明天上午会去你家。

Wǒ míngtiān shàngwǔ huì qù nǐ jiā.

To give a more accurate word order structure on how to structure words should go as followed:

Sbj + Tme + Mnr + Plc + Neg + Aux + Vrb + Cmp + Obj

(subject, adverbials, negative, auxiliary verb, verb, complement, object)

Overuse of le “了”

The overuse of the word "le" is more common than you think. The main cause for this is due to the fact English-speakers use tense more often than compared to its use in Mandarin. The strict use of conjugation in English that assures you use words in past tense with –ed endings. Because of this, some English speakers think it's necessary to use "le" when the want to express past tense. Due to inexperience, this often leads to the miss use of "le" and "guò". Overuse of "了" when describing the past.

I went to climb the mountain yesterday and I was very happy.

我昨天去爬山,玩得很高兴了。

Wǒ zuótiān qù páshān ,wánde hěn gāoxìng le.

我昨天去爬山,玩得很高兴。

Wǒ zuótiān qù páshān ,wánde hěn gāoxìng.

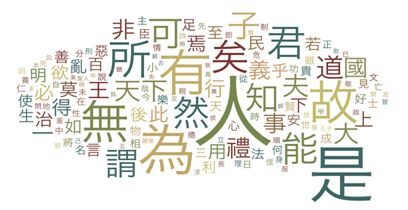

Overuse of shi “是”

For new learners who are native English speakers, they might make this mistake because it is easy to assume that "shi" is interchangeable with “is” but they later learn this is not the case. English speakers sometimes use "shi", in sentences where it's not necessary, the word should be replaced with another, or it can be omitted but the meaning is still the same. Here are a few examples:

This is a very good movie.

这部电影是非常好看。

Zhèbù diànyǐng shì fēicháng hǎokàn.

这部电影非常好看。

Zhèbù diànyǐng fēicháng hǎokàn.

She is married.

她是结婚。

Tā shì jiéhūn.

她结婚了。

Tā jiéhūn le.

Not putting sentences in question form

Sometimes you could put Chinese native listeners in a lost state, but leaving the pondering as to whether or not you just said a statement or asked a questions, especially without the correct tone to match what you've said.

Some language students might leave out the question words and particles which are needed in spoken Chinese. In written form you can get away with this by simply adding a question mark at the end of your sentence but the question particle is needed in spoken Chinese. This habit can form in spoken Chinese if students rely on the tone of their voice to imply that they are asking a curious question similar to likes of English. Remember to use the question particles, question words such as and grammar structures that suggest a question is being asked, otherwise the Chinese person you are speaking to might thought you were telling them some interesting information instead.

Compliment:

你跑得快。

Nǐ pǎo de kuài.

You run fast.

Question:

你跑得快吗?

Nǐ pǎo de kuài ma?

Do you run fast?

Relying on direct translation

One aspect that is difficult for some English speakers to understand is that when learning to speak Chinese, not all things translate over well from English to Chinese and vice-versa. When Chinese people and Westerners try learning both languages by searching words from a dictionary and using word-for-word translation, this method leads to a lot of language misuse.

Some Chinese words and idioms have historical meanings in China and cultural meanings that are unknown in other parts of the world. 3 and 4 Chinese character idioms can sometimes have simple one sentence translations and others can only be interpreted through context or a short story describing it.

The only way to combat this bad habit is to change your mindset. Otherwise you will often be disappointed when a word cannot be explained with a translated counterpart. Learning Chinese by the direct translation approach will often be ineffective with more complex language.

Adding too many words

One area of difficulty for expats learning Chinese, is using too many words in attempts to convey their message as if they are using Chinese the same way they would use English or another language. This leads many students to use more words than necessary for some simple commands.

One example for our explanation, asking for a menu at a restaurant.

English: May I have a menu, please.

Chinese: 菜单Càidān

Some English speakers may attempt saying something along the lines of:

你可以给我菜单吗?

Nǐ kěyǐ gěiwǒ càidān ma.

But this meaning can be summed entirely by just telling a waiter: 菜单càidān

Character confusion

This mistake is all too common but for good reason. To the untrained eye, Chinese characters can look like Hieroglyphics, and undistinguishable, but even some students who know how to read and write characters, sometimes have mishaps when they aren't looking closely, and miss key details. For instance, if you don't look carefully while texting Chinese, you could input these mistakes when talking with Chinese friends, co-workers and etc.

Some famous examples that are often confused by language students:

Bīng 氷 vs Yǒng永

Gěn艮 vs Liáng良

Tǔ土 vs Shì士

Shé佘 vs Yú余

One good way to overcome these mistakes is to pay attention to detail, and study stroke orders that will allow you to recognize the subtle differences between characters that from a distant glance looks similar.

Since 2004, more than 50,000 non-native speakers from over 130 countries have chosen Mandarin House as their Chinese language partner. Our experience and expertise in helping them achieve their Chinese goals is second-to-none. You can follow our WeChat to find out more about Mandarin House locations in Beijing, Shanghai, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Chengdu and the effective E-learning solution.