(Photo: itpcas.cas.cn)

By studying 140-million-year-old oyster fossils, a joint team of Chinese and international scientists has uncovered clues about Earth’s climate during the Early Cretaceous period, challenging the singular narrative of steady warming trend and offering new insights into future global climate predictions.

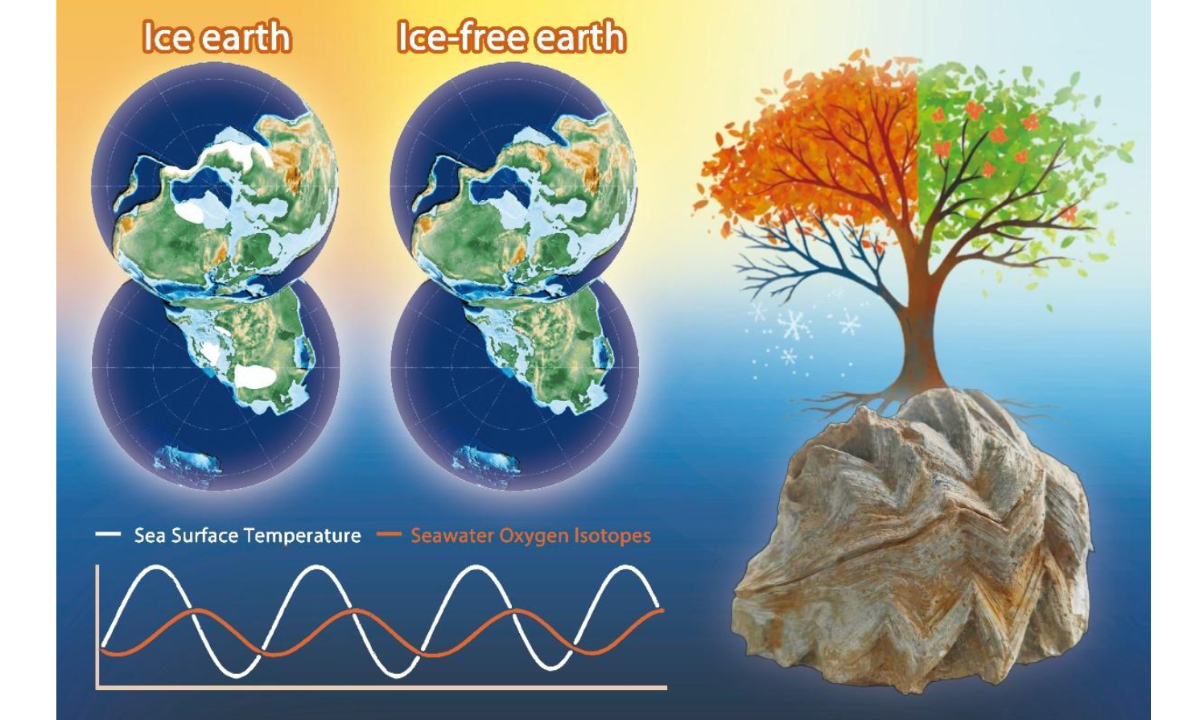

Using oyster shell fossils records and combined with high-resolution climate simulations, the study has, for the first time, reconstructed the seasonal fluctuations in sea surface temperatures during the greenhouse periods of 140 million years ago. It revealed marked seasonal temperature differences and periodic glacial melt events during the Early Cretaceous period (approximately 139.8 to 132.9 million years ago).

This discovery challenges the long-held belief that seasonal variations were weak and glacial activity was rare during greenhouse periods, revealing the complexity and variability of Earth’s climate under greenhouse conditions, offering a new perspective for understanding long-term climate evolution.

The research findings were published online in the international scientific journal Science Advances on May 3.

The research team, including Chinese scientists from the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research of Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), has found that during the Early Cretaceous period – an era dominated by dinosaurs and characterized by a greenhouse climate – Earth still experienced significant seasonal temperature swings, and may even have had periodic glaciation, in stark contrast to the current state of permanent polar ice sheets.

Researchers explained that oyster shells and similar accretionary organisms grow in annual patterns resembling tree rings, forming alternating light and dark bands. During the hot summer months, the shells grow faster and are more porous, creating “light bands,” while in the colder winter months, growth of the shells slows and the structure of the shells becomes denser, forming “dark bands.”

These shell-bearing organisms act as natural time recorders, preserving detailed evidence of Earth’s climate and ecosystem evolution. Studying them can help guide future ecological research, according to Ding Lin, an academician at the CAS.

In this study, the research team analyzed growth lines on oyster fossils and used advanced instruments to examine their chemical composition, confirming that the fossils were well-preserved.

The researchers found that during the Early Cretaceous, winter ocean temperatures in the mid-latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere were 10 to 15 C lower than in summer – comparable to the seasonal temperature differences in that region today.

Climate simulations further suggested that seasonal glacial meltwater may have flowed into the oceans at the time, similar to the summer melting of glaciers on Greenland’s ice sheet today.

The study also underscores that climate change is not always a steady warming trend. Greenhouse gas increases can intensify seasonal extremes and increase the likelihood of unpredictable weather.

The study found that the brief glaciation events that occurred 140 million years ago may have been triggered by a combination of large-scale volcanic activity and changes in Earth’s orbit – reminding that local geological events, alongside human activity, could cause unexpected cooling even in today’s warming world.

Ding Lin said that this study opens a new window into ancient climate history. By challenging the simplistic view of the greenhouse climate, the research not only reshapes the understanding of Earth’s distant past but also provides valuable reference points for predicting future global warming trends.